Masai Mara National Park, Kenya

The Masai Mara National Park was founded in 1948. Mara means “spotted” in the Maasai language. The park is located in southern Kenya and is the northern part of the Serengeti plain in Tanzania. Masai Mara covers an area of 1510 sq. km. Among tourists, it is considered the most popular national park in Kenya.

Its grandiose landscapes are magnificent! Two rivers flow through the territory: Mara and Talek, along which acacia forests grow. In the north and east, foothills begin, there are thorny shrubs and stunted trees.

In terms of the richness of the animal world, the Masai Mara can only be compared with the Serengeti and Ngorongoro National Parks in Tanzania. About 80 species of mammals and about 450 species of birds live here.

During the great migration, which takes place from August to September, more than 200 thousand zebras, about 500 thousand Thompson’s gazelles, 1.3 million wildebeest move along the Masai Mara.

This is an amazing show! This national park attracts tourists from all over the world with its “big five” animals: buffalo, lion, elephant, giraffe, rhinoceros. Among the representatives of the bird world there are: ostrich, various types of eagles, vultures, cormorants, etc.

According to Cellphoneexplorer.com, the Masai Mara National Park is one of the most famous reserves of the Black Continent. The ban on hunting that exists here does not apply only to the Maasai tribes living on these lands.

Elephant tusk, rhinoceros horn, lion skin – for a long time these hunting trophies brought good money. And the better things went for hunters and resellers, the less chance of survival the African wildlife had. The number of the largest and most beautiful inhabitants of the savannah was rapidly declining – in the middle of the twentieth century it seemed that only a miracle could save the richest animal world of Africa from extermination. And it happened.

No, the demand for ivory and leopard fur did not fall on the “black market” and poachers did not sheath their guns – it’s just that in the prosperous countries of Europe and America people appeared who were ready to pay a lot of money for the pleasure of seeing the same lions or elephants not on TV and not in the zoo, but in natural habitats. For the first time in the history of African exploration, it was not the destruction of an animal that promised commercial gain, but its preservation in its integrity. Tourism has become the savior of the African fauna.

Many states of the Black Continent have tried to use the opportunities that have opened up in connection with this. Significant funds were spent on the creation and support of national parks, a total ban on hunting and trading in any hunting trophies was introduced. These measures practically eliminated poaching and allowed wild animals to get rid of the “genetic” fear of humans.

National parks with open spaces have become especially attractive, allowing you to “hunt down” an animal and drive up to it as close as possible. Among these parks, the Masai Mara is the most popular.

However, since wildlife has become one of the main sources of income, the Maasai tribes – nomadic pastoralists, who owned these lands for almost three centuries, had to make room: maximum freedom in the park was given to animals. And they did not fail to take advantage of this.

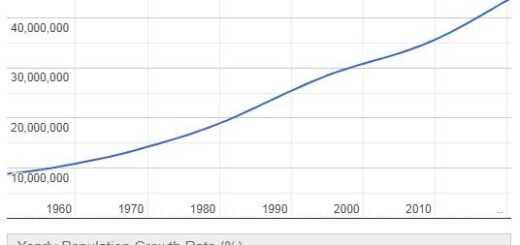

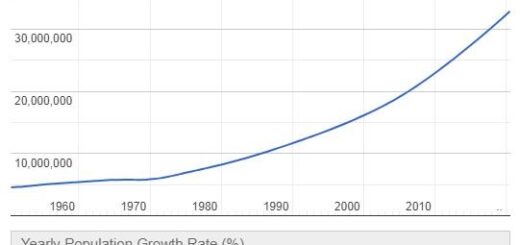

The number of white-bearded wildebeest in the Masai Mara and the Serengeti has grown in twenty years from 250 thousand to one and a half million! The open border between Tanzania and Kenya allows these animals, in company with 250,000 zebras and 500,000 Thomson’s gazelles, to migrate freely in search of better pastures, keeping the entire Serengeti Mara ecosystem in a stable balance.

The famous wildebeest migration begins in June, when the rainy season comes to an end in the Masai Mara and vegetation is renewed in the expanses of the savannas. One and a half million herd of wildebeest, replenished by 400 thousand newborns, leaves the Serengeti scorched by the sun and rushes to Kenya, to the Masai Mara. This path, repeated twice a year in opposite directions, is full of drama. Thousands of animals become victims of lions, jackals and hyenas, drown while crossing the Mara River, filling the stomachs of crocodiles and carrion marabou, die under the hooves of their own kind during panic attacks characteristic of wildebeest. Only one of their three cubs born in the Serengeti will be able to return at the end of the year.

Countless herds, like hordes of locusts, completely cover the yellow hills – then, stretching for many kilometers in a narrow chain, with the dullness of an hourglass “flow” from place to place. The spectacle of migrating wildebeest has become one of the wonders of the wild.

This “bacchanalia” of wild herbivores, which delights connoisseurs of nature, is treated with reasonable indignation by the Maasai. Antelopes pose a threat to their own herds, destroy pastures, poison the few sources of water with droppings. In 1968, a Maasai MP in Kenya accused the government of putting animals first and people second in its policies. This demarche is indicative: for all the primitive way of life, the Masai constantly prove their resilience and learn to take advantage of the forced proximity to civilization.

Despite the external restraint characteristic of the Maasai, bordering on hostility, more is known about them than about many other African tribes.

The Masai are a highly pragmatic people who quickly realized the senselessness and even destructiveness of confrontation with Western civilization, which is increasingly penetrating Africa.

Without betraying their inner world, they themselves admitted ethnographers to themselves, allowing them to examine themselves for a certain reward.

The widespread opinion about the spitefulness of the Maasai is apparently connected with their sharply negative reaction to unauthorized photography: for a picture taken without permission and for free, they can be pierced with a spear. However, this is only a reaction to the unceremonious intrusion into their lives.

The Maasai believe in a rain god called Ngai. According to legend, Ngai had three sons. He gave the first an arrow, and he became a hunter, the second – a hoe, and he became a peasant, and the third took the last thing left – a stick to graze the cattle. He was the father of all Maasai. They believe that they are called to preserve cattle throughout the earth, and to replenish their herds, without a twinge of conscience, they take animals from neighboring tribes. Livestock for the Maasai is the foundation of their whole life. The main food is milk and blood (Maasai meat is not eaten, but used for ritual purposes). The skins are used for clothes, shoes and beds. Dung is a means for building, urine is for healing. The animal’s blood is extracted from the jugular vein, pierced with an arrow, and poured into a gourd vessel, where it is mixed with milk. The animal does not die at the same time – the wound is carefully treated, and it heals.

Maasai families live in inkangs – round settlements, shaped like a kraal, surrounded by a fence of bushes with such thorns that neither predator nor enemy will turn up. Inside the inkangi is a circle of 10 to 20 low and cramped huts, in which tall Masai are forced to squat or lie down. Huts are woven from thin trunks and rods and caulked with fresh cow dung, which hardens in the sun and differs from clay only in smell.

The Masai (or Maasai in their native language – Maa) ethnically belong to the group of Nilotic people – tall people from the Nile Valley. The Masai themselves appeared in Kenya presumably in the 16th-17th centuries, almost simultaneously with the Portuguese, who landed on the eastern coast of the continent. Oppression of the colonialists, tribal wars, smallpox, cholera, loss of livestock and famine – since the end of the 19th century, difficult times have come for the Masai people. In 1910, the construction of the Kenya-Uganda railway cut off a significant part of their ancestral lands. The Maasai suffered even greater losses half a century later, when the redistribution of territories began in the country, which, by the way, was associated with the organization of the Masai Mara National Park. One can only wonder how and why, being in direct contact with civilization, the Masai manage to maintain their terrifying, in the opinion of Europeans,

Maasai society has a clear three-tier structure based on age categories: youth – warrior – elder. Once every 6 – 8 years, the elders appoint another initiation – a rite of passage for young men who have reached the age of 15 – 18 into warriors. After going through a series of trials and the circumcision procedure, recruit soldiers devote themselves entirely to the main male duties: protecting livestock, caring for its increase (including by robbing neighbors), searching for new pastures, etc. A warrior with experience gets the right to marry, and over time can move to the rank of elder. Married women have their own responsibilities: raising children, cooking, milking cows, repairing homes. Despite the existence of polygamy, within age groups, men and women are virtually equal. The Maasai do not have a concept of divorce, and the elder decides all disputes.

Most severely punished is disrespect for the elder: convicted of this sin can be subjected to a curse. The damage from the curse extends mainly not to the person of the perpetrator, but to his livestock, since this is more sensitive for the Maasai. However, the excessive zeal of the elders in punishment is not encouraged: the curse, like a boomerang, can return and hit the elder himself. Guilt is removed by repentance and the payment of a fine in the amount of one heifer – after that the curse can be considered exhausted.

Masai Mara National Park is a unique place. Nobody is a threat here. And life and death are in those proportions that have been established from time immemorial by nature itself. Maybe that’s why everyone seems happy here: both people and animals.