Norway 2001

Yearbook 2001

Norway. In the spring, foot-and-mouth disease in Europe resulted in Norway closing the border to Sweden for some food, despite the fact that neither country was affected.

The populist Progress Party (FRP), which was the largest party in opinion polls last autumn, lost half of its sympathizers at the beginning of the year. The decline followed a bitter power struggle between party leader Carl I. Hagen and primarily the party’s Oslo district. The party board suspended or excluded a number of senior members. The settlement was seen as an attempt by Hagen to clear out the most outspoken immigrant opponents to have the party accepted as part of an upcoming bourgeois government. However, the government dream was shattered when Frp’s vice-president was accused of rape and forced to resign.

- Abbreviationfinder: lists typical abbreviations and country overview of Norway, including bordering countries, geography, history, politics, and economics.

The ruling Labor Party (AP), which wanted to modernize the public sector, made only temporary public opinion gains following Frp’s decline. Høyre, who promised to improve the worn-out schools and at the same time lower taxes, took the initiative instead and became the largest party in the public opinion during the summer. Thus there were three prime ministerial candidates: Høyre’s leader Jan Petersen, the incumbent Head of Government Jens Stoltenberg, Ap, and the former central government’s Prime Minister Kjell Magne Bondevik, Christian People’s Party, Krf.

The parliamentary elections in September were won by Høyre, who went from 23 to 38 seats. Ap became a loser with a decline from 65 to 43 seats. The left wing was partially offset by the Socialist Left Party more than doubling its mandate from 9 to 23, but the AP government chose to resign. The center shrunk and was no longer a realistic government alternative. The right leader then invited two of the middle parties, Krf and Venstre, to talks about a broad bourgeois government, but the negotiations failed. Bondevik, whose Krf received 22 seats in the elections, took over the initiative and managed one of the three parties around a joint program. With Bondevik as prime minister, Petersen as foreign minister and Left’s leader Lars Sponheim as agriculture minister, a minority government was formed, which in the Storting became dependent on the Progress Party’s 26 mandate.

The election movement was unusually quiet, as the nation was occupied a few weeks before the election by the royal wedding held between Crown Prince Haakon and Mette-Marit Tjessem Høiby.

Finland’s largest asset manager Sampo tried during the year in vain to acquire the Norwegian insurance group Storebrand. The AP government and a majority in the Storting wanted Den norske Bank to take over Storebrand and keep the company in Norwegian ownership. The fight was described in the Norwegian press as a “international fight”, as the Finnish state is a partner in Sampo.

The Norwegian state oil company Statoil was partially privatized in June on the Oslo Stock Exchange. The company’s share price fell soon, and in the autumn oil prices fell below the level that was the basis for the government’s 2002 budget proposal.

The major Kværner Group was threatened with bankruptcy but was offered the rescue of the Russian oil company Yukos Oil, which wanted to become its largest shareholder. However, it was financier Kjell Inge Røkke who managed to take over that role and start a rescue operation that was expected to give Kvaerner 3.5 billion Norwegian kroner. Thus, Røkke had definitely established himself as Norway’s industrial king.

Economy

This class structure is determined by the structure of the Norwegian economy, where the industrial sector is today dominated by the large export companies, while the agricultural sector is targeted to the domestic market, which is supplemented by extensive imports. Thus, for the industry, the Norwegian market is too small, for agriculture too large. Both sectors contribute in their own way to making the Norwegian economy highly outward and therefore cyclically sensitive.

| Headquarters | Turnover | |

| 1 Norsk Hydro AS | Oslo | 5166 |

| 2 Aker group | Oslo | 3035 |

| 3 Borregaard AS | Sarpsborg | 2501 |

| 4 Elkem-Spigerverket AS | Oslo | 2447 |

| 5 Kvaerner Industrier AS | Oslo | 2178 |

| 6 AS Norwegian Esso | Oslo | 2169 |

| 7 AS Årdal and Sunndal Works | Oslo | 2085 |

| 8 AS Norske Shell | Oslo | 1542 |

| 9 AS Norcem | Oslo | 1357 |

| 10 The Norwegian State Oil Company AS Statoil | Stavanger | 1298 |

| 11 Standard Telephone and Kabelfabrik AS | Oslo | 1153 |

| 12 Dyno Industrier AS | Oslo | 1010 |

| 13 Ing. F. Selmer AS | Oslo | 1002 |

| 14 Mos Rosenberg Verft AS | Jeloy | 865 |

| 15 AS Norsk Jernverk | Mo i Rana | 864 |

| 16 Norske Skogindustrier AS | Skogn | 863 |

| 17 AS Norsk Elektrisk & Brown Boveri | Oslo | 832 |

| 18 Electro Union AS | Bergen | 815 |

| 19 Engineer Thor Furuholmen | Oslo | 796 |

| 20 Bergens Mekaniske Verksteder AS | Bergen | 724 |

| 21 AS Kongsberg Arms Factory | Kongsberg | 710 |

| 22 AS Denofa and Lilleborg Fabriker | Oslo | 680 |

| 23 Siemens AS | Oslo | 676 |

| 24 Tandbergs Radiofabrik AS | Oslo | 666 |

| 25 AS Jotun groups | Sandefjord | 662 |

| The 25 largest industrial and mining companies in Norway in 1976. Turnover in millions of DKK. Source: Norway’s 1000 largest companies, 1977. |

||

The long coastline, a limited agricultural area and much rainfall in the mountains give Norway the raw materials fish, wood and electricity. These again form the starting point for virtually the entire country’s industry. Over time, it has shifted from fish to wood and from wood products to electricity, where raw material extraction and processing form the expanding sector: Raw materials which, by being supplied with energy, become marketable on the world market – ferro alloys, aluminum, cement etc. Over the past 20 years these commodities are overtaken by oil and gas production, making Norway today the world’s 10th largest exporter of these energy sources.

Around the 3 commodity groups fish, wood and electricity, refining and support industries have been formed: shipbuilding and mechanical industries around the fisheries sector, timber cargo and other shipping; chemical industry for food and wood fiber utilization; different metal industry around energy utilization. In addition, the building and construction industry is responsible for road, dam and house production, which, after developing on the domestic market, is now looking for export opportunities.

The basic structure of industry must not be seen as sectoral in actual business. Once started, the industry has shown the ability to quickly switch. Norsk Hydro began as a pure harnesser of electricity and has since been active in the chemical industry, metal extraction and now oil. The shipbuilding industry was developed to meet the needs of ships in fisheries and timber exports, and has now switched to production of oil extraction equipment, etc. different sectors. The Norwegian economic structure provides little opportunity for actual economies of scale. An exception is the cement production in Norcem.

The large industry in Norway therefore consists mainly of large groups with several feet to stand on. Whether these new composite “group” groups will be able to demonstrate a similar ability to adapt in the future, as the individual companies did during the construction of the current structure, is an industrial policy key issue in the changes that will take place in the future.

Agriculture and its place in the Norwegian economy are also characterized by product adaptation. It is too simple to claim that agriculture today is a purely domestic business. Agricultural products go through many types of circuits. In the complicated interplay of animal and vegetable production, there are many products that go out of the country in the form of dairy products and are again brought in as meat. Ifht. calorie accounting today, imports are expected to surpass exports, even though agricultural policy professes a form of self-sufficiency. The agricultural sector as a gross industry contributes greatly to making the Norwegian economy foreign-oriented, which is reinforced by the fact that agricultural machinery and tools are practically exclusively imported goods.

Alongside the constant dependence on foreign countries, the Norwegian economy has another special feature: It is heavily regulated in public. Clean private business has probably never existed in Norway. Although each production company may appear to be privately owned or operated, the framework conditions surrounding the profession are in most cases created through public regulation. The regulations together are quite extensive. Alongside the weak upper class, Norway has a strong state.

The industry’s dependence on the public sector is mainly due to two factors: Resource regulation and market protection. Both ocean and energy resources are public, and their exploitation depends on state concession. Fishing and shipping can only be run on the basis of a strong public infrastructure – lighthouse and port services, supervision and quota regulation. The use of hydropower is tightly regulated by the public, which gives the public a major influence on the determination of such an important factor as the price of electricity.

The company in these areas can therefore not be conceived without state involvement – far beyond the traditional public services such as police, health care and education.

Furthermore, Norwegian industry is very much developed on the basis of public privileges through a strict customs policy and market protection. Major groups such as Hydro, Electrochemical, Borregaard or Norcem are all built up through systematic public initiatives. The same goes for large parts of the consumer goods industry – from food to electronics.

This state participation is not of a new date. In the 19th century, customs policy was adapted to the union with Sweden in a way that was to ensure Norwegian production. In the 20th century, the major revisions to customs duties have always been oriented towards protecting Norwegian products.

Only with the creation of EFTA cooperation in the 1950s did this change. Some goods came on the free list: Footwear and textiles lost customs protection in Norway and production had to be discontinued. During the market negotiations in the 1960s and 1970s, the business community’s contradictory attitudes to the customs issue became clear. What, for one producer, is protection from outside competition, for another, more expensive commodities and for the third, destroyed export markets as a result of reprisals from other countries.

During the Nordic market negotiations, the business community in Norway emerged as an opponent of a Nordic common market (Nordek). The European single market efforts, on the other hand, seemed overwhelmingly attractive and led to a comprehensive campaign by the business community on this matter. But even within the EC, Norwegian producers must have secured continued state aid for production protection and market security, in addition to direct industrial support at the company level, which has been launched as the special counter-cyclical measures of the 1970s.

This is even more true for agriculture, which is economically not just a foreclosed profession, but an industry cut off from the market at all. Agriculture is part of the Norwegian state-owned economy through a network of customs, subsidy and support schemes. Even at the producer level, agriculture cannot be considered as a “private” occupation: in fact, each farmer is as dependent on public financing as any government official.

The Norwegian economy had long shown a higher employment share in agriculture than other western industrialized countries. But in the 1950s and ’60s, the number of farms and jobs declined sharply. When this development slowed down in the 1970s, it was mainly due to public initiatives that stimulated land utilization and made it competitive with other employment opportunities. Today, agriculture employs 7.5% of the working population – still a high number in the western context.

The special position of agriculture in the Norwegian economy is reflected in several factors. The Norwegian political system is primarily business oriented, and has traditionally been sensitive to the demands of agricultural interests.

In addition, for the people of Norway, agriculture has always played a role far beyond the individual farm. Every home in the villages and small towns had previously had a small piece of potatoes, an outhouse with room for chickens and pigs and perhaps a cowshed business which provided a substantial dietary supplement for most people.

Traditionally, Norwegian families in the countryside and small towns have nourished themselves by combining economics: wage income through man, food supplements from land and animals driven by women and sometimes children. However, with the increasing local concentration of the population in residential buildings, this opportunity for primary business subsidies to the family economy is weakened. But 60% of households in expanding settlements such as Hol and Tynset continue to eat food from the family’s own production, and half of all the fruit eaten in Norway comes from villa gardens.

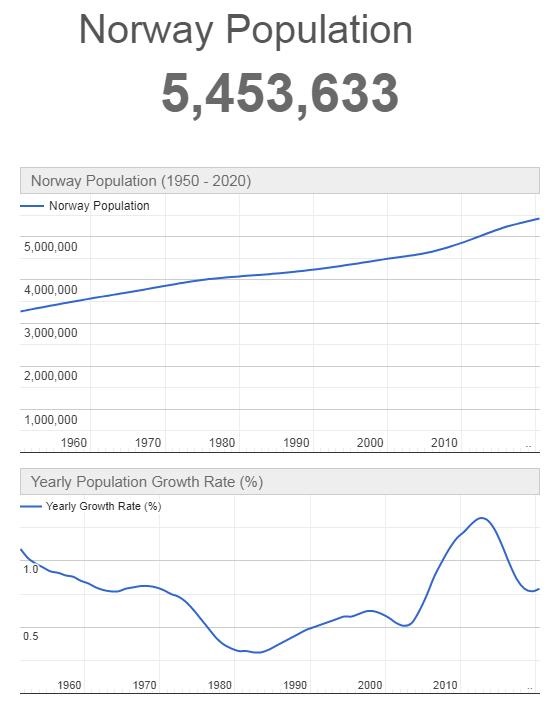

Population 2001

According to Countryaah, the population of Norway in 2001 was 4,632,253, ranking number 116 in the world. The population growth rate was 0.580% yearly, and the population density was 12.6821 people per km2.