Croatia 2001

Yearbook 2001

Croatia. The question of how Croatia should deal with allegations of Croatian war crimes during the 1991-95 civil war caused deep division during the year and threatened stability in the country. Nationalists and war veterans felt that no Croats were guilty of war crimes, as they fought a war of freedom and defended the homeland. That attitude was also officially supported by former President Franjo Tudjman. But in February, a court in Rijeka issued a warrant for General Mirko Norać, who was suspected of assaulting civilian Serbs. He was the highest ranking person so far identified for war crimes during the war. Norać went underground and 100,000 people demonstrated in Split against the attempts to arrest him. See anycountyprivateschools.com for vocational training in Croatia.

President Stipe Mesić warned that ultranationalists were trying to overthrow the government. After a week Norać surrendered to the authorities against the promise that the trial would be held in K. and not at the UN Criminal Tribunal in The Hague. The tribunal also stated that there was no prosecution against him. The trial began in June but was soon upgraded indefinitely due to technicalities.

- Abbreviationfinder: lists typical abbreviations and country overview of Croatia, including bordering countries, geography, history, politics, and economics.

In July, however, the government decided to extradite two other Croatian generals to The Hague at the tribunal’s request. The decision caused a split in the government coalition, and four ministers resigned in protest. They all belonged to the coalition’s second largest party, the Social Liberal HSLS. One of the two generals surrendered himself to the UN Court but denied all charges. The other general had disappeared.

Several suspected war criminals were later arrested, and protests against the reform-friendly government continued. Prime Minister Ivica Račan was accused by the right-wing opposition of treason for his cooperation with the Hague Tribunal.

In late January, Croatia nonetheless tried to recapture the Krajina enclave, however unsuccessfully, but it led to the cease-fire. The United Nations Security Council unanimously agreed in February to extend the mandate for “The Blue Berets” posted in Croatia.

In June 1994, Croatia reintroduced the “kuna”, which had been the coin foothold used by the puppet government during the German occupation during World War II in the country. The replaced “denar” that had been introduced after independence.

It met opposition from the opposition, but Tudjman emphasized that the Croatian word “kuna” means miserable, and referred to the 11th century when furs and skins were the means of payment.

The opposition also questioned the decision to change the road, school and place names dedicated to the anti-fascist martyrs.

Pope John Paul’s 2nd visit to Croatia, 10th. and September 11, helped give the country an international “boost”. The Serbian rebels and the Croatian government agreed on a reopening of the Zagreb-Belgrade land link, the opening of the Adria oil pipeline and the restoration of the water and electricity supply to the Serbs in the occupied territories.

Croats managed to gain control of inflation, although industrial output was declining and unemployment remained at 20%. The number of university-educated and skilled craftsmen who emigrated increased dramatically during the year.

In January 1995, Croatia warned the UN that it would not extend the mandate of peacekeeping forces that expired on March 31. According to Tudjman, the 12,000 “blue berets” effectively protected the Serbs in Krajina, controlling 27% of the total Croatian land area. The Serbian and Croatian forces began preparations for a new war, while the UN declared that a withdrawal of the peacekeeping force could lead to the worst crisis in Europe so far since 1945.

On April 13, Serbian forces bombed the airport of Dubrovnik, and ten days later they blocked the road between Zagreb and Belgrade in western Slavonia. The Croatian side regained control of the area following a swift military action in May; Immediately after, Zagreb was exposed to Serbian bombings.

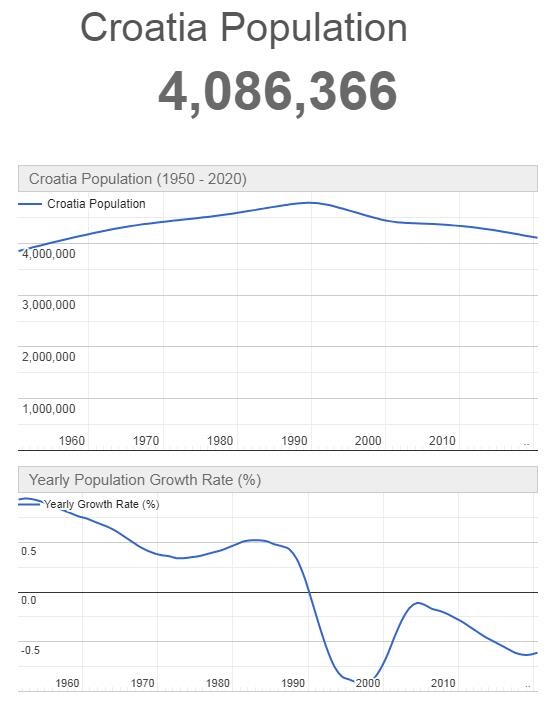

Population 2001

According to Countryaah, the population of Croatia in 2001 was 4,377,947, ranking number 118 in the world. The population growth rate was -0.230% yearly, and the population density was 78.2355 people per km2.