Sweden 2001

Sweden during the Second World War

At the outbreak of the war in 1939, the Swedish government issued a declaration of neutrality and recommended enhanced defense preparedness. Although there was no acute threat, the strategic situation was dramatically aggravated by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on August 23, 1939. This was evident when the Soviet Union, during the autumn, took a first step towards incorporating the Baltic republics by forcing military bases and into ultimate forms require land exits of Finland. The subsequent winter war (November 30, 1939 – March 12, 1940) put Swedish foreign policy to the test. When Secretary of State Rickard Sandler, which advocated Swedish-Finnish cooperation on the Åland defense, did not receive support from the government’s majority, the result was a government crisis and the formation of a unifying government with representatives of the four largest parties (December 13, 1939). The Prime Minister was Per Albin Hansson and the Foreign Minister became a professional diplomat, Christian Günther. The new government supported Finland in the form of humanitarian aid, credit and weapons supplies, and a Swedish volunteer force participated in the fighting. On the other hand, Britain’s and France’s request for a breakthrough for a rescue corps to Finland was rejected, taking into account the risk of a German counter-attack that would have made Scandinavia a war scene.

- Abbreviationfinder: lists typical abbreviations and country overview of Sweden, including bordering countries, geography, history, politics, and economics.

The German attack on Denmark and Norway in April 1940, Sweden faced German demands for transit through the country of troops and military equipment. As long as the war in Norway was going on, these demands were rejected, but after the fighting ended, the government felt compelled to allow unarmed German permits through transit between Germany and Norway and partly between southern Norway and Northern Norway, the so-called horseshoe traffic (June 1940). The decision on transit traffic became the beginning of a concession policy, which culminated when the government in June 1941 allowed the transit of a fully equipped division, the Engelbrecht Division, from Norway to Finland (see Midsummer crisis)). When the German war accident reversed in 1942–43, the course was changed. In July 1943, the Permit Agreement was terminated without Germany taking any hostile action. At the end of the war, foreign policy was increasingly adapted to the demands of the Allies. Iron ore exports to Germany were gradually cut, and in the autumn of 1944, all German-Swedish trade exchange ceased. Danish and Norwegian police forces received training in Sweden, and in the spring of 1945, Sweden was prepared to require military intervention in Norway and Denmark if required.

By the end of the war, Sweden, through effective economic and military preparedness and a realistic, sometimes undocumented neutrality policy, had managed to avoid being involved in combat operations. This was an advantage not only for Sweden itself, but also for the Allies, who could use Sweden as a sanctuary in the area dominated by Germany. This was especially true of the Danish and Norwegian resistance movements and of the Jewish refugees from Denmark who in 1943 applied for this. Thanks to effective crisis management, supply problems became less extensive than during the First World War. Rationing could not be avoided, and private motoring ceased almost entirely, but the population suffered neither from starvation nor from any other real need. The state of health was better and death rates lower than during the peacetime.

The remission policy against Germany during the first years of the war was subjected to undue criticism by a number of anti-Nazi newspapers, including the Gothenburg Trade and Maritime Magazine with Torgny Segerstedt as editor-in-chief and after all! published by Ture Nerman. The government responded with repressive measures such as confiscation and transport bans, and Karl Gerhard’s review “Golden Rain” (1940), which contained the coup “The infamous horse from Troja” was banned by the police after pressure from the German legation. The following year, another critic of the concession policy, Vilhelm Moberg, published, “Ride tonight!” (1941). The book’s parallels between resistance and apathy towards German demands in the 1650s and at the same time avoided being censored and received great attention. On the other hand, those who had a positive attitude to Germany, with explorer Sven Hedin in the lead, became increasingly difficult to assert themselves after the German defeat at Stalingrad and after information about the Holocaust began to reach the public. Instead, anti-Nazi messages in words and images became more and more common.

After the war, neutrality policy continued to be a key element of Swedish politics. The fact that the majority government was able to keep Sweden out of the Second World War was considered by many to be good. However, from the late 1980s, and especially after the publication of Maria-Pia Boëthius’s critical study of Swedish politics in 1939–45, “Honor and Conscience” (1991), however, Swedish refugee policy, the remission towards Germany, the permittal traffic, restrictions in freedom of the press and the Swedish handling of Jewish assets during World War II have been recurring topics of debate.

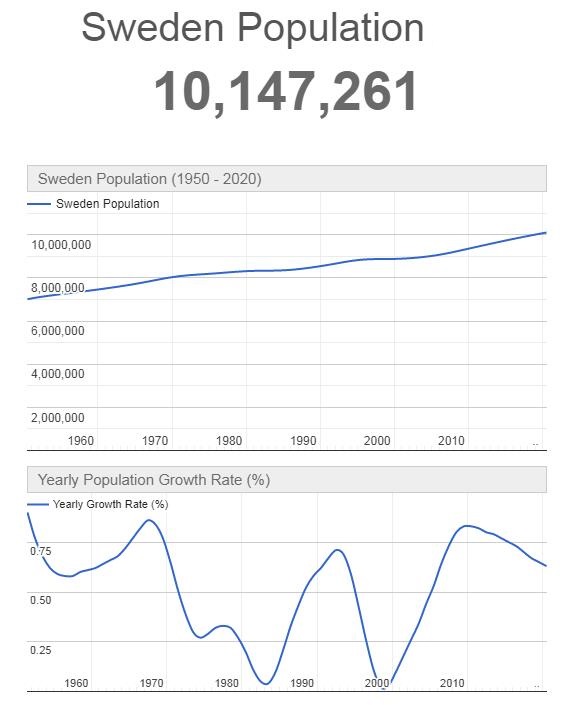

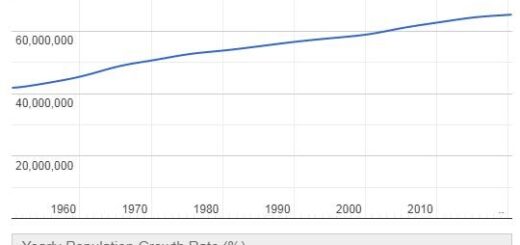

Population 2001

According to Countryaah, the population of Sweden in 2001 was 9,038,512, ranking number 88 in the world. The population growth rate was 0.350% yearly, and the population density was 22.0272 people per km2.