Slovenia 2001

Yearbook 2001

Slovenia. After several weeks of negotiations, Prime Minister Janez Drnovšek and his Croatian colleague Ivica Racan reached an agreement that resolved most of the disputes that remained since both republics broke out of former Yugoslavia in 1991 that the countries jointly manage the nuclear power plant in Krsko, which was built during the communist era and partly financed with Croatian money. Four disputed villages remained in Croatian control. To enter into force, the settlement must be approved by the parliaments of both countries.

On 7 July 1991, with mediation from the European Union, a ceasefire agreement was concluded following negotiations between the federal authorities and Slovenian representatives; the agreement was signed on the island of Brioni. The agreement recognized the sovereignty of the Yugoslav population groups, but suspended the entry into force of Slovenian independence for a period of three months. At the same time, the Federal President’s control over the Federal Army and a Slovenian police control over the border region were recognized.

- Abbreviationfinder: lists typical abbreviations and country overview of Slovenia, including bordering countries, geography, history, politics, and economics.

Following the Brioni agreement, the customs authority at Slovenia’s borders was handed over to the Slovenian police, while possibly the repayment of customs duties was to be decided by an internal account between the individual former republics of Yugoslavia. The Federal Army remained at the “green border”, where there were no border posts until the work of transferring competence to the Slovenes had been completed; 3 months were allocated for this.

To support the ceasefire, the agreement provided for unconditional withdrawal of federal army units from the prisons and a demobilization of Slovenian troops in the national defense; In addition, the army was withdrawn from the roads and a release was made of all prisoners on both sides.

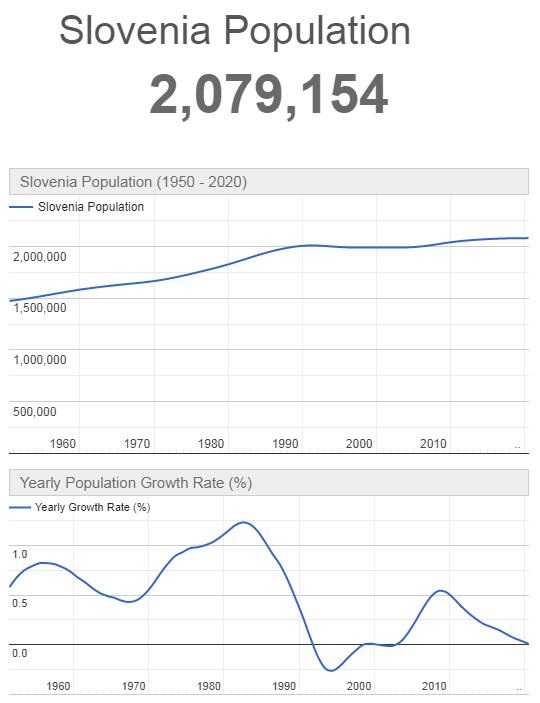

While still part of Yugoslavia, the Slovenes accounted for almost 8% – or 1.9 million – of the total population, while industrial production accounted for 25% of the Federal Republic’s total production.

From December 1991 to January 1992, EU member states recognized Slovenia and Croatia as independent nations, yet civil war broke out in the latter. The EU threatened to impose financial sanctions on Belgrade unless hostilities were stopped. Thanks to the homogeneity of the population, the development in Slovenia became the least bloody among the former republics in Yugoslavia.

Recognition of Slovenia was also the most obvious as it controlled its own borders, controlled its own army and issued its own currency. After the withdrawal of the Yugoslav Federal Army, under the leadership of Milan Kucan, the government again attempted an economic recovery, virtually without the assistance of the former Yugoslav government.

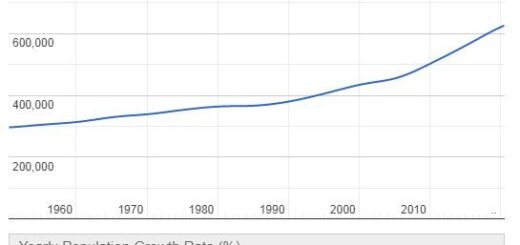

Population 2001

According to Countryaah, the population of Slovenia in 2001 was 1,994,865, ranking number 145 in the world. The population growth rate was 0.070% yearly, and the population density was 99.0554 people per km2.

Literature. – The picture of Slovenian literature of the years 2005-2014 is lively and composite. In an era of constantly increasing globalizing pressure, this nation fits into the European and Slavic (mittel) context with its own undeniable specificity. With the collapse of walls and ideologies and the commodification of art, writing looks for new languages here.

Its strength does not seem to fail even today that Slovenia was a sovereign state and has resolved the question of identity. Publishing places hundreds of good quality novels, short stories, poems and children’s literature on the market every year. The poets aim at linguistic experimentation with original and varied verses. Kajetan Kovič (1931-2014), also a poet for children, and Tomaž Šalamun (1941-2014), initiator of ludism, have recently passed away. Today still active we must remember Ciril Zlobec (b. 1925; Vse daljave niso daleč, 2011, trans. It. Close distances. Italian encounters and friendships of a Slovenian poet, 2012), Vladimir Kos (b.1924), Jože Snoj (b.1934), also prose writer, Niko Grafenauer (b.1940), poet also for children. Virtuosos of the word are Milan Dekleva (b.1946), also prose writer, Milan Jesih (b.1950), with translations in anthologies, and Boris A. Novak (b.1953), also playwrights, Miroslav Košuta (b.1936; translated in Italian, for example, in the anthology L’altra anima di Trieste, 2008) and Svetlana Makarovič (b. 1939), also author of fairy tales; and again Milan Vincetič (b. 1957), Brane Mozetič (b. 1958; Banalije, 2003, trans. it. Banality, 2011), Aleš Debeljak (b. 1961), Uroš Zupan (b. 1963), Peter Semolič (b. 1967) and the poetesses Ifigenija Simonović (b.1957), Maja Vidmar (b.1961 ; translated, for example, in the anthology Decametron, 2009) and Barbara Korun (b.1964), with bilingual editions. Among the youngest, to mention Primož Čučnik (b. 1971; translated into Italian in several collections, eg Decametron, 2009, and Loro return in the evening, 2011), AlešŠteger (b. 1973; Berlin, 2007, trans. It. Berlin, 2009), Miklavž Komelj (b. 1973; translated into anthologies, e.g. Decametron, 2009, and They come back in the evening, 2011) and the authors Taja Kramberger (b. 1970), with multilingual editions, and Stanka Hrastelj (n. 1975; translated into Italian, for example, in the anthology Loro tornano la sera, 2011).

The panorama of prose is also vast. After years of short and fragmentary postmodernist stories, the novel returns and tends towards a new realism (v.). The generational span is still wide, think of the Trieste-born Boris Pahor (b. 1913) and Alojz Rebula (b. 1924), today mostly essayists. Both translated in previous years, the last decade saw a sharp increase of the Italian editions of their works and interest in their work: they cite the first edition of the release the same year as the Slovenian So I lived. Biography of a century (it. By Tako sem živel. Stoletje Borisa Pahorja, 2013), of the second Night on the Isonzo (2011, it. By Nokturno za Primorsko, 2004) and The source of the four rivers (2013, selection of passages from various works by the author, also available online. In addition, Drago Jančar (b. 1948), author also theatrical, well-known at home and abroad; Vlado Žabot (n.. 1958), Jani Virk (b. 1962), Andrej E. Skubic (b. 1967), DušanŠarotar (b. 1968); more translated into Italian, Miha Mazzini (b. 1961; Telesni čuvaj, 2004, trad. It. They called me the dog, 2011), Andrej Blatnik (b. 1963; Spremeni me, 2008, trans. It. Cambiami, 2014) and the authors Maja Novak (b. 1960), Janja Vidmar (b. 1962) – who write prose for children – and Suzana Tratnik (b.1963); all three translated into Italian, the last two with independent volumes, Moja Nina (2004; trad. it. My Nina, 2007) for Vidmar, a selection of short stories from various Slovenian editions for Tratnik (Maximum discretion, 2009). Younger Aleš Čar (b. 1971), Jurij Hudolin (b. 1973) and Nina Kokelj (b. 1971), author also for children, present in collections in Italian. Poets and / or directors, Evald Flisar (b.1945), Ivo Svetina (b.1948), Emil Filipčič (b.1951), Milan Kleč (b.1954), Andrej Rozman (b.1955), Vinko Möderndorfer (b. 1958), Feri Lainšček (b. 1959) and Matjaž Zupančič (b. 1959), write fiction, plays and screenplays. Among other things, a selection of plays by Flisar (Three dramas, 2012) and two volumes by Lainšček (La ragazza della Mura, 2009, transl. It. By Muriša) have been published in Italian., 2006) and The story of Lutvija and the red-hot nail (2009, trans. It. By Nedotakljivi, 2007). Among the youngest are Goran Vojnović (b. 1980) and Nejc Gazvoda (b. 1985).